Radical Cystectomy

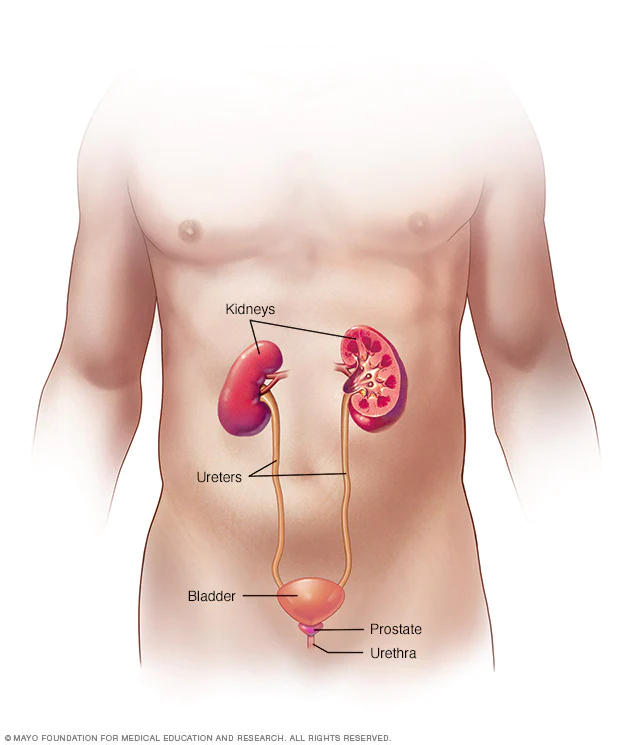

The procedure to remove the entire bladder is called a radical cystectomy. In men, this typically includes removal of the prostate and seminal vesicles. In women, radical cystectomy usually includes removal of the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes and part of the vagina.

After removing your bladder, your surgeon also needs to create a new way to store urine and have it leave your body. This is called urinary diversion. Your surgeon will discuss the options for urinary diversion that may be appropriate for you.

A radical cystectomy is performed to treat cancer that has invaded muscle tissue of the bladder or recurrent noninvasive bladder cancer. A partial cystectomy, although rarely performed, is used to remove a cancerous tumor in an isolated portion of the bladder. A simple cystectomy — removal of only the bladder — may be a treatment for noncancerous (benign) conditions.

Why it's Done

Your health care provider may recommend cystectomy to treat:

Cancer that begins in or spreads to the bladder. Irregularities in the urinary system present at birth. Neurological or inflammatory disorders that affect the urinary system. What type of cystectomy and reconstruction you have depends on many things, such as the reason for surgery, your overall health, and your preferences and care needs.

Risks

Cystectomy is a complex surgery. It involves the manipulation of many internal organs in your abdomen. Because of this, cystectomy carries with it certain risks, including:

- Bleeding

- Blood clots in the legs

- Blood clots that travel to the lungs or heart

- Infection

- Poor wound healing

- Damage to nearby organs or tissues

- Organ damage due to the body’s overreaction to infection (sepsis)

- Rarely, death related to complications from surgery

Other risks associated with urinary diversion vary depending on the procedure, but complications may include:

- Dehydration

- Decline in kidney function

- Imbalance in essential minerals

- Vitamin B-12 deficiency

- Urinary tract infection

- Kidney stones

- Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence)

- A blockage that keeps food or liquid from passing through your intestines (bowel obstruction)

- A blockage in one of the tubes that carries urine from the kidneys (ureter blockage)

Some complications may be life-threatening or require hospitalization. You may need another surgery to correct problems. Your surgical team will provide you with information about when to call your care team or when to go the emergency room during your recovery.

How You Prepare

Before your cystectomy, you will talk to your surgeon, your anesthesiologist and other members of the care team about your health and any factors that may affect the surgery. These factors may include:

- Long-term medical conditions

- Drug allergies

- Previous reactions to anesthesia

- Obstructive sleep apnea

You should also review with the surgical team your use of the following:

- Prescription and nonprescription drugs

- Vitamins, herbal medicines or other dietary supplements

- Alcohol

- Cigarettes

- Recreational drugs

- Caffeinated beverages

If you smoke, talk to your health care provider about what help you may need to quit. Smoking can affect your recovery from anesthesia and surgery.

What you can expect

Options for cystectomy surgery include:

- Open surgery. This approach uses a single incision on your abdomen to access the pelvis and bladder.

- Minimally invasive surgery. With minimally invasive surgery, the surgeon makes several small incisions in the abdomen where special surgical tools are inserted to access the abdominal cavity. This type of surgery is also called laparoscopic surgery.

- Robotic surgery. Robotic surgery is a type of minimally invasive surgery. The surgeon sits at a console and remotely operates robotic surgical tools.

Results

A cystectomy and urinary diversion are important life-extending treatments. But these surgeries do cause lifelong changes in both urinary and sexual function that can affect your quality of life. With time and support, you can learn to manage these transitions. Ask your health care team if there are community resources or support groups that may help you.