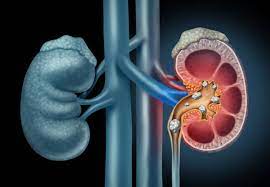

Kidney & Ureter Stone Surgery

Kidney stone disease (nephrolithiasis) is a common problem in primary care practice. Approximately 10 to 20 percent of all kidney stones require surgical removal, which is determined based upon the presence of symptoms and the size and location of the stones.

General Principels

Goals of surgical therapy — The overall goals of surgical stone management are relief of patient discomfort, clearance of infection, and reversal of kidney function impairment associated with kidney or ureteral stones.

Important outcomes that should be discussed with patients when deciding upon surgery include the following:

Treatment success – Treatment success for ureteral or kidney stone surgery is generally defined as complete stone removal, or the stone-free rate (SFR). Although there is no consensus definition for SFR, commonly used definitions include the absence of residual stones or the presence of residual stone fragments ≤4 mm in size as determined by follow-up imaging studies such as kidney ultrasound, plain abdominal imaging, digital tomosynthesis, or low-dose, noncontrast computed tomography (CT). Achieving a stone-free status is important, since small residual stone fragments, particularly those >4 mm, may grow and ultimately result in return visits to the emergency department or require additional surgical intervention . Additional important measures of treatment success include the need for retreatment or secondary procedures.

Risk of complications – The benefits of surgical stone removal must be weighed against the risk for morbidity and complications. Procedures that offer the highest SFRs (such as ureteroscopy [URS] and percutaneous nephrolithotomy [PNL]) also have higher complication rates. Complications associated with specific procedures are discussed elsewhere in this topic.

Quality of life – Following surgical stone removal, patients should expect to experience an improvement in quality of life, such as resolution of pain associated with kidney stones or the prevention of future symptomatic stone episodes. However, quality of life may also be reduced by the use of postoperative ureteral stents (most commonly after URS) that can cause patient discomfort.

Indications and contraindications

In general, the main indications for surgical treatment of stones include pain, infection, and urinary tract obstruction. No specific surgical therapy is required for asymptomatic stones, particularly those that are less than 5 mm in diameter. However, surgical stone removal may be reasonable for patients with asymptomatic stones who are frequent travelers or pilots, those considering pregnancy, or those who wish to avoid symptomatic stone episodes that may require emergency surgery. Specific indications for emergency and elective surgery include the following:

Indications for emergency surgery – Urgent decompression of the collecting system is indicated in the following clinical scenarios:

• Patients with obstructing stones and suspected or confirmed urinary tract infection (UTI)

• Patients with bilateral obstruction and acute kidney injury (AKI)

• Patients with unilateral obstruction with AKI in a solitary functioning kidney

Indications for elective surgery – Among adult patients who do not have an emergency indication for surgery, specific indications for surgical stone treatment are provided by the 2016 American Urological Association/Endourological Society guidelines, which recommend surgical management in the following clinical settings.

• Ureteral stones >10 mm

• Uncomplicated distal ureteral stones ≤10 mm that have not passed after four to six weeks of observation, with or without medical expulsive therapy (MET) .

• Symptomatic kidney stones in patients without any other etiology for pain

• Pregnant patients with ureteral or kidney stones in whom observation has failed

• Persistent kidney obstruction related to stones

• Recurrent UTI related to stones

Contraindications – There are no absolute contraindications to stone removal surgery. However, shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) should not be performed in patients who are obese, are pregnant, or have an uncontrolled bleeding diathesis.

Ureteral stones

URS and shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) are the most commonly performed surgical modalities for the removal of ureteral stones. In patients who do not require emergency surgery and have indications for elective stone removal the choice of surgical procedure depends primarily upon the size and location of the stones but may also be influenced by other patient characteristics (such as pregnancy, urinary tract anatomy, or stone composition) and comorbidities (eg, obesity, bleeding diathesis).

● The overall SFR was significantly higher with URS as compared with SWL (90 versus 72 percent).

● For stones ≤10 mm, SFRs were superior for URS compared with SWL at all locations in the ureter: 85 versus 67 percent for proximal ureteral stones, 91 versus 75 percent for mid-ureteral stones, and 94 versus 74 percent for distal ureteral stones.

● For stones >10 mm, SFRs were comparable between SWL and URS in the proximal ureter (74 versus 79 percent, respectively) but were superior for URS in the middle and distal ureter (83 versus 67 percent for mid-ureteral stones and 92 versus 71 percent for distal ureteral stones).

● Rates of UTI, sepsis, ureteral stricture, or ureteral avulsion were comparable between SWL and URS. However, ureteral perforation occurred more frequently with URS than with SWL (3 versus 0 percent). Another meta-analysis also reported higher procedure-related complication rates with URS compared with SWL (16 versus 9 percent).

URS is more likely to successfully treat patients with ureteral stones in a single procedure, reducing the need for additional procedures [9]. In one analysis, the mean numbers of primary URS procedures needed to treat stones in the proximal, middle, and distal ureter were 1.01, 1.00, and 1.00, respectively; by contrast, the corresponding mean numbers of primary SWL procedures were 1.34, 1.29, and 1.26, respectively [9].

Kidney stones

SWL, URS, and PNL are the most commonly used surgical modalities for patients who require removal of kidney stones. In patients who do not require emergency surgery and have indications for elective stone removal the choice of surgical procedure depends primarily upon the size and location of the stones but may also be influenced by other patient characteristics (such as pregnancy, urinary tract anatomy, or stone composition) and comorbidities (eg, obesity, bleeding diathesis).

● In general, SFRs for both SWL and URS decrease with increasing stone size, whereas the efficacy of PNL is minimally affected by stone size.

● For stones <20 mm located in upper pole, middle calyx, or pelvis of the kidney, SWL and URS offer SFRs of approximately 50 to 80 percent . In one meta-analysis that compared SWL and URS for kidney stones 10 to 20 mm in size, URS provided a higher SFR and lower retreatment rate without an increase in the rate of complications .

● For stones located in the lower pole of the kidney, particularly those >10 mm, URS and PNL offer substantially higher SFRs compared with SWL, with a moderately increased risk of complications. In one systematic review, for lower pole stones between 10 and 20 mm in size, the median SFR was 81 percent for URS, 87 percent for PNL, and 58 percent for SWL . For lower pole stones >20 mm, the median SFR was 83 percent with URS, 71 percent for PNL, and 10 percent for SWL. In general, although the ability of SWL to disintegrate stones in the lower pole of the kidney is not limited compared with other locations, the fragments frequently remain in the calyx and cause recurrent stone formation.

● For stones >20 mm, PNL offers the highest SFRs (approximately 80 to 95 percent for upper and middle pole stones and 70 to 80 percent for lower pole stones).